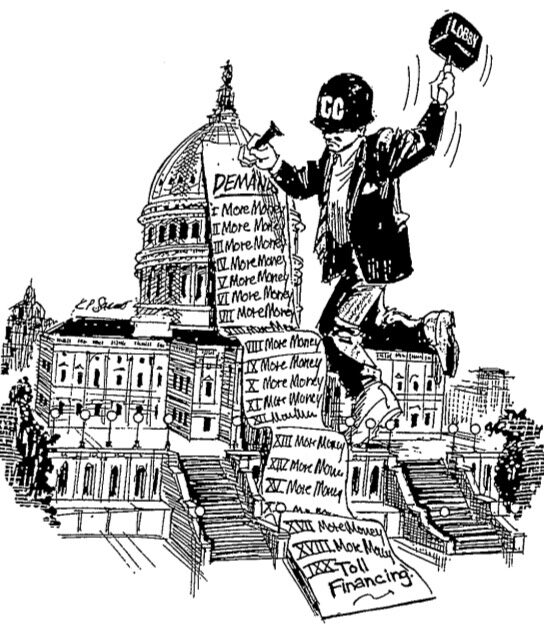

In June 2025, Indiana legislators made history. They agreed to finance the long-needed reconstruction and modernization of their aging Interstate highways, using a reliable funding source: 21st-century electronic tolling.

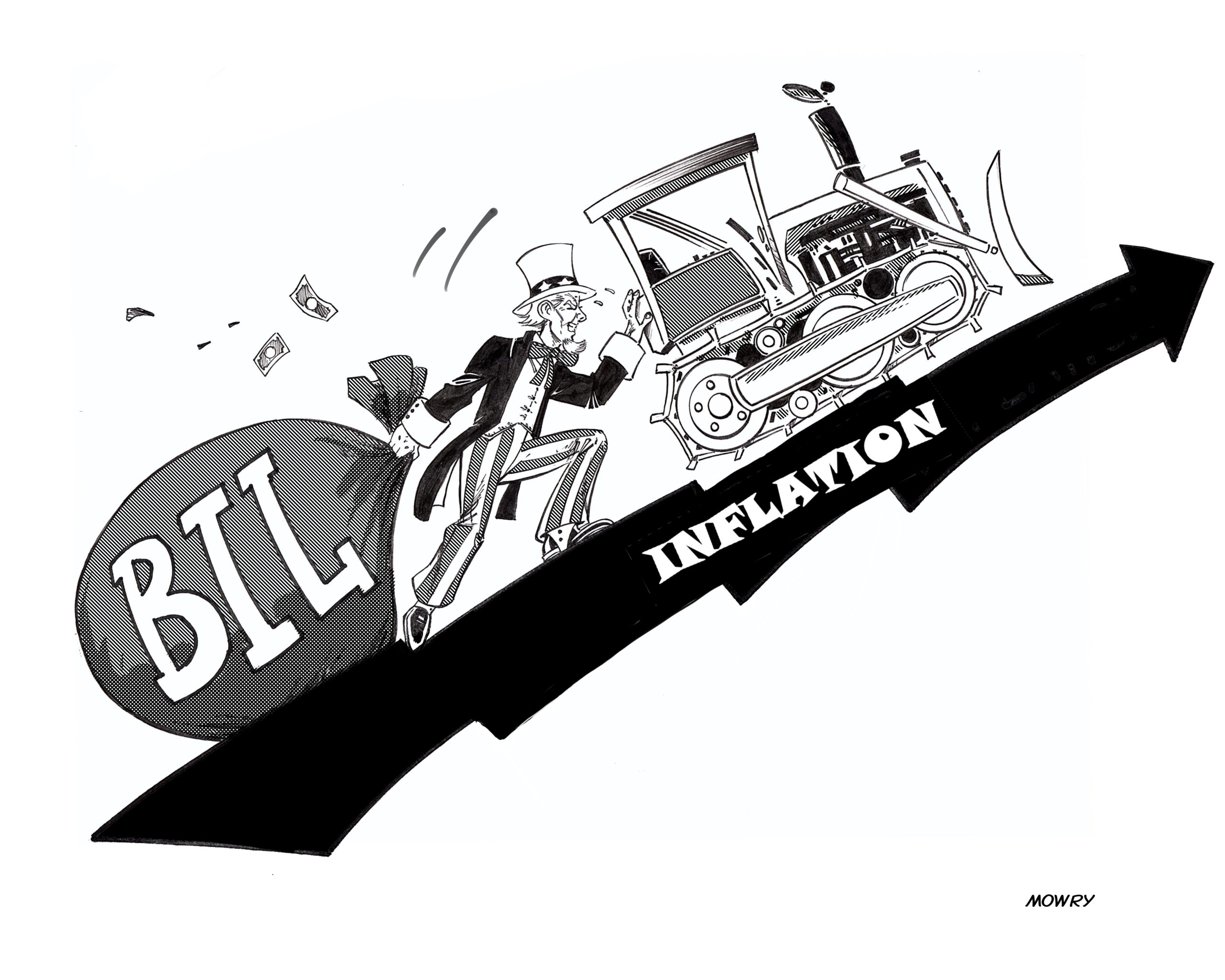

Rebuilding these vital corridors for personal travel and interstate commerce will be the largest set of public works improvements in Indiana’s history. Each Interstate reconstruction is likely to be a mega-project, costing a billion dollars or more. Megaprojects, alas, have a long history of cost overruns and late completions. A key question for Indiana policymakers is: Who should bear the risks of these megaprojects? Taxpayers or investors?

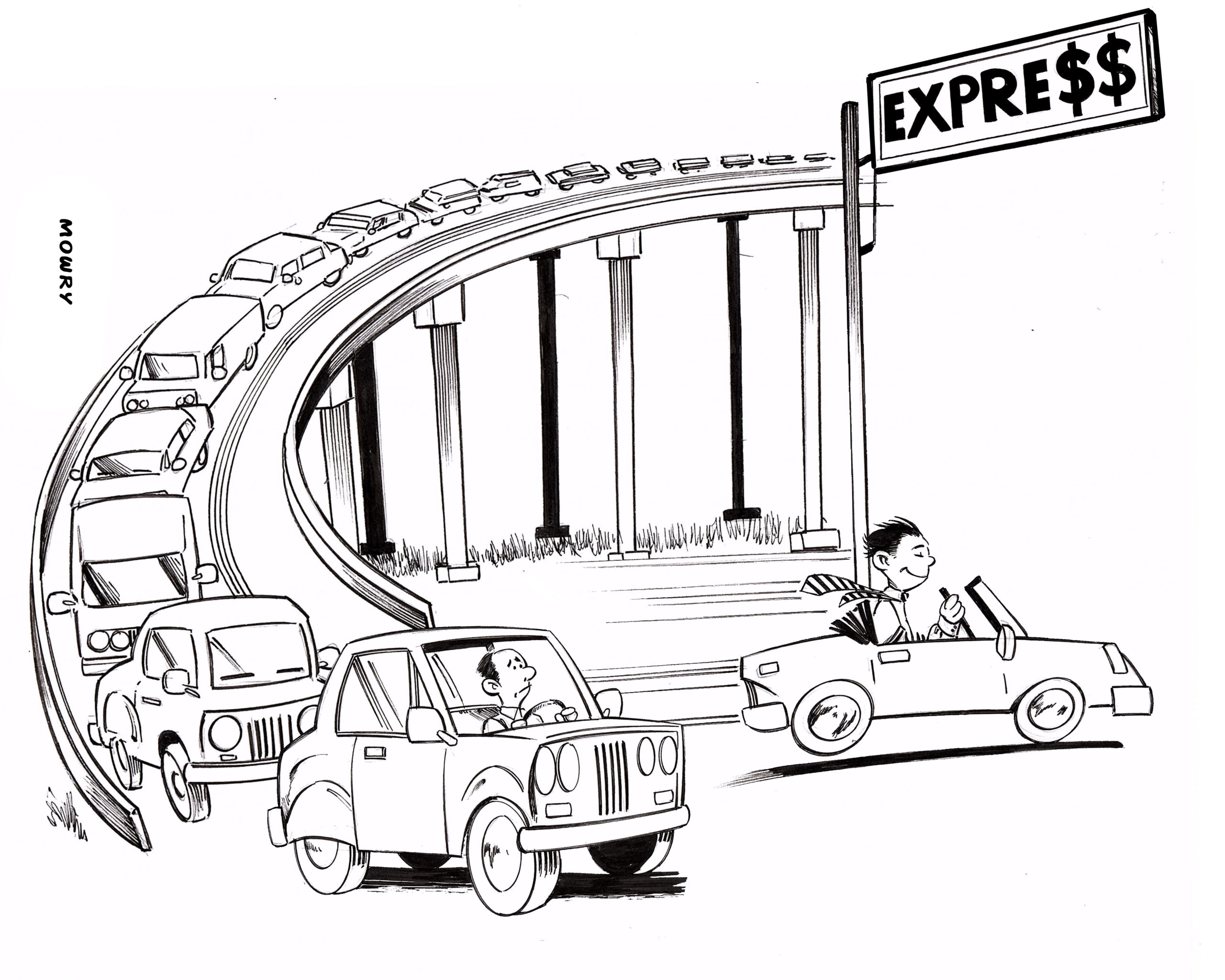

Since these projects will make use of toll financing, there are two alternatives. One would be for the state to create a new state toll agency, in which the financing comes almost entirely from state-issued revenue bonds, and the project is done by design-build contractors, supervised by INDOT. This is how state toll agencies in Florida and Texas procure most additions to their toll roads.

The other alternative is using a long-term public-private partnership (P3) for each project, in which the winning bidder will design, build, finance, operate, and maintain (DBFOM) the Interstate, via a long-term agreement with clearly-stated performance measures and state oversight. In large P3 megaprojects, construction cost overruns are generally the responsibility of the private partner, rather than taxpayers. The private partner is contractually bound to performance measures over the life of the long-term agreement, which could be 50 to 75 years.

Indiana policymakers should carefully analyze the risks involved in choosing the state’s approach to toll-finance Interstate reconstruction and modernization.

Megaprojects like these are recognized worldwide as risky, for example, as documented in the book Megaprojects and Risk by Oxford scholar Bent Flyvbjerg (Cambridge University Press, 2003). The two most significant risks are generally large cost overruns and (for toll projects) overly optimistic projections of revenue. Another megaproject risk is late completion.

When a megaproject is managed by a state agency, the excess costs are ultimately borne by the taxpayers. Late completion of a highway megaproject means that motorists and truckers will have to endure construction conditions for more months or years than they expected.

If Indiana already had a state toll agency with a track record of successful projects, the megaproject risks noted here might be reduced. But since a new toll agency would have to be created if Indiana takes this approach, there would be other risks. The new agency would have no track record, so buyers of its toll revenue bonds would likely expect higher interest rates on the new agency’s bond issues to compensate them for start-up-agency risks. Alternatively, the state might decide to back those bonds by the “full faith and credit of the state.” That means Indiana taxpayers would be the ultimate backstop for the inexperienced toll agency.

If Indiana decided instead to deliver its tolled Interstate reconstruction and modernization via long-term DBFOM P3s, there would be important risk transfers, from taxpayers to investors. The typical long-term P3 concession includes the private-sector partner assuming most or all of the construction- cost risk and late-completion risk. Secondly, instead of the project being financed 100% by revenue bonds and state funds, the typical long-term P3 highway project averages 14% from government, 26% from a federal TIFIA loan, 28% from tax-exempt private activity bonds (PABs), and 31% from equity investors.

The TIFIA loans and PABs are non-recourse instruments, meaning the state bears no responsibility for repaying them; they are the sole responsibility of the P3 concession company. And if a recession occurs after the project is finished and in operation, and traffic (and hence toll revenue) falls below projections, the P3’s “patient equity” is available to ensure regular payments to the bondholders. These are very important transfers of risk from the state to the P3 entity.

While Indiana has no recent experience operating a state toll agency, it does have the advantage of an entity that has managed procurements of long-term P3 concessions: the Indiana Finance Authority. IFA managed the long-term P3 lease of the existing Indiana Toll Road in 2005. The original P3 company engaged in very aggressive financing (at its own risk) and ended up extremely over-extended during the recession in 2014 and was unable to make good on its debt service. Fortunately, those were non-recourse bonds, so the state was not obligated to compensate the bondholders.

Instead, IFA worked with the creditors to re-lease the Toll Road’s long-term concession. Within six months IFA announced a winning bid for the remaining 66 years of the 75-year concession. That sum was large enough that the creditors recovered 99% of their losses. The winning bidder was IFM Investors, owned by an array of public pension funds. Its conservative buyout of the concession consisted of 57% equity and only 43% debt (compared with the original company’s 15% equity and 85% debt).

There were two other U.S. P3 toll road bankruptcy filings in the early 2000s: the South Bay Expressway near San Diego and the SH 130 toll road between Austin and San Antonio. There was no taxpayer bailout in either case. In more-recent years, bond rating agencies and consulting firms have insisted on more-conservative financing of P3 toll road projects—and there have been no more bankruptcies.

Today’s conservative P3 financing contrasts with typical state all-debt financing. The latter puts the state and its taxpayers at risk when the economy tanks and traffic (especially lucrative truck traffic) declines. The equity invested by P3 companies is sometimes referred to as “patient equity” because it is generally in last place in the distribution of toll revenues. The equity provides a cushion during recessions compared with all-debt financing.

To sum up, creating a state toll agency from scratch would be a risky proposition, especially as it would have to finance up to five Interstate toll-financed reconstruction projects. With an experienced entity such as the Indiana Finance Authority managing successive P3 competitions, considerable risk would be transferred from the state to investors.

How Indiana chooses to proceed will be watched by other state governments that have done (or been part of) large-scale studies of Interstate tolling. These include Connecticut, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin.