Priced managed lanes are having their moment. For decades after their mid-20th-century conception, only a handful of projects reached operation, and most were regarded as risky bets. They were difficult to forecast, dependent on government subsidies, and met with skepticism from both investors and the public. Over the past fifteen years, the narrative has shifted. Today, procuring and operating a public-private partnership (P3) priced managed lane (PML) on the right corridor is approaching routine.

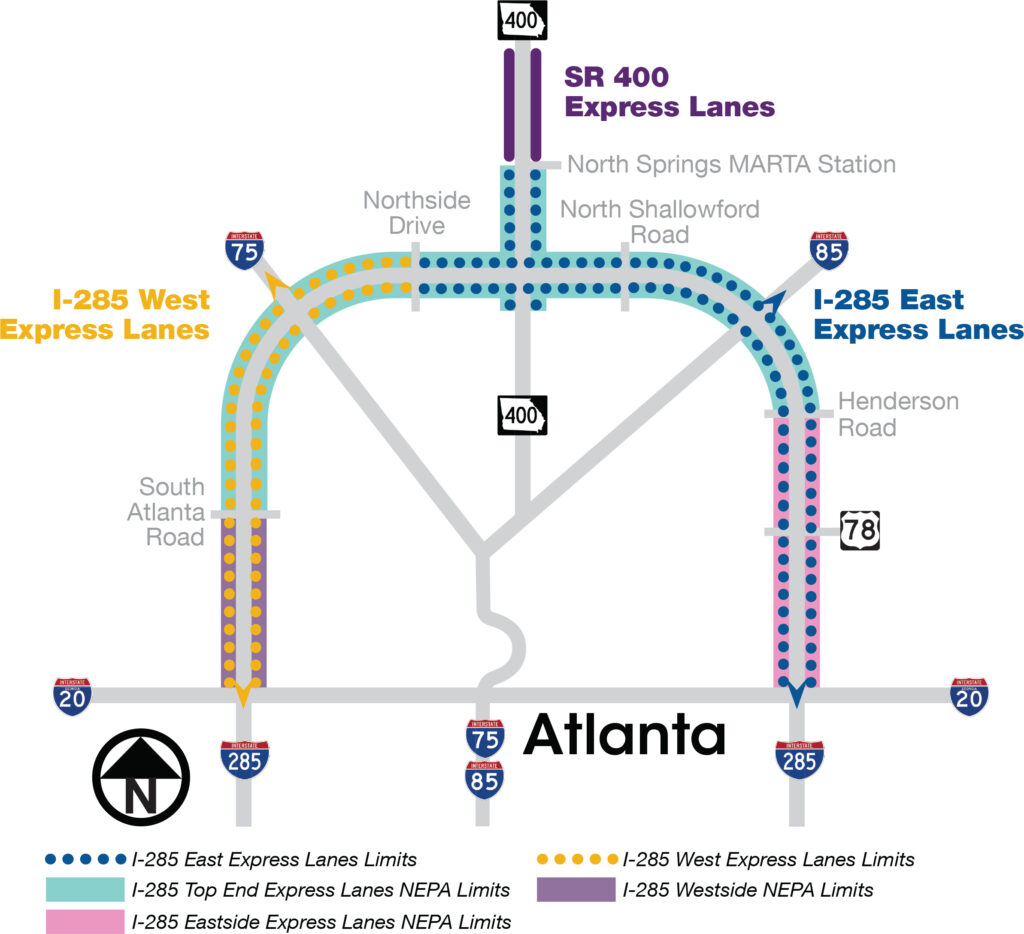

Recent developments illustrate this transformation. Georgia’s 15-mile-long SR-400 Express Lanes recently closed with the winning consortium covering the $4.7 billion construction cost and a $3.8 billion upfront payment. These figures would have seemed impossible a decade ago. Rating agencies, once skeptical, are now upgrading the credit of operational assets, recognizing their sustained performance through COVID-19’s disruptions. P3 PML projects have routinely exceeded revenue expectations and investor appetite for managed lane debt is robust.

Three developments explain why priced managed lanes have become viable and attractive to both owners and investors. First, familiarity breeds acceptance. With dozens of facilities now operating, priced managed lanes are becoming normalized. The public accepts, if not always enthusiastically, that reliable mobility comes at a price.

Second, drivers demonstrate willingness to pay that far exceeds traditional value-of-time calculations. Express lanes deliver value for time savings, but drivers significantly value benefits like reliability, safety, and choice. This has led to new pricing models and exposed previously unexplored revenue potential.

Third, operational assets have matured and proven resilient. Financial results have largely outperformed early expectations, with revenues rebounding after the pandemic. Private operators have converged a playbook of real-time dynamic pricing, extremely reliable experience, and maximizing the potential user base through connectivity.

Yet PML projects are not universal solutions. Owners must make a series of critical (and often early) decisions that define performance, bankability, and public value.

This article is the first in a three-part series examining those commercial choices. We focus on the commercial choices faced by owners, including toll-setting policy, the handling of discounts, and toll violation processing. A companion piece [next month] addresses planning choices, including connectivity, design, and large truck accommodation. The third paper examines how to address evolving technology within a multi-decade agreement, addressing connected vehicles, advanced payment systems, and evolving digital systems. Together, these lessons help public owners translate the hard-won experience of the past fifteen years into better projects and outcomes.

Authors note: This represents one perspective among many. Our mission is helping public agencies navigate these complex decisions. We synthesize market experience and surface lessons from operational projects to generate public value and foster a robust infrastructure market.

Commercial Consideration #1: Toll Policy

Toll policy is the most consequential commercial decision for a P3 priced managed lane project or program. Tolls are the defining feature of PMLs—they ensure operational success, drive headlines, attract public curiosity, and are the subject of political attention. Tolls are also the primary lever for managing congestion when express lane demand pushes against capacity. And perhaps most obviously, tolls fund projects and generate returns for developer-operators.

Good toll policy balances the tension between consumer protection, operational integrity, and revenue generation. Successful policy accomplishes these three things at once. First, it enables pricing to preserve the operational performance of the PMLs when needed. Second, it gives the developer reasonable headroom to generate revenue responsibly, and third, it protects users from unfair pricing by establishing clear rules on how prices are set.

The central challenge is placing limits on pricing without compromising reliability and, to an extent, feasibility of the project. Hard caps offer one solution. Public facilities like the I‑405 in Seattle and I‑95 in Florida let prices vary in real time but never exceed a stated maximum, typically about ten or fifteen dollars per trip. A hard cap gives the public an absolute promise of the highest toll they might pay, but it prevents the project from managing demand at critical times. This can lead to persistent unreliability, eroding confidence and dampening revenue precisely when the lanes are most valuable.

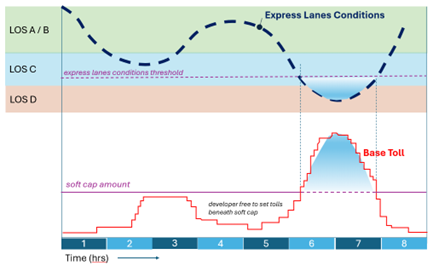

A proven alternative is the soft cap. First deployed across the Dallas-Fort Worth PML network and recently adopted as the basis for SR-400’s pricing policy, the soft cap sets a toll threshold—usually a rate per mile–up to which the developer may charge under any conditions. Prices may exceed the threshold only when predefined operational triggers are met, usually low speeds or high volumes in the express lanes. Pricing above the soft cap is permitted only while those conditions persist in real time, and toll rates must return below the threshold once they clear.

Congestion on an express lane can take hours to unwind. Effective soft caps set trigger conditions so prices rise before performance degrades. An owner guaranteeing express lane speeds of at least 50 mph might set the trigger at Level of Service C, around 55 to 60 mph, or when volume reaches approximately 1,500 passenger-car equivalents per lane per hour—about 80% of capacity on most PMLs. Under this regime, owners cannot promise exactly what users will pay, but they can confidently say that drivers determine prices beyond the soft cap through their own choices about how and when to use the lanes.

Smart toll policy also preserves flexibility to capture value during midday and busy weekends. Time savings may be modest then, but an uncrowded alternative to the general purpose lanes is attractive to a meaningful share of drivers. Fifteen years of experience shows that drivers pay for more than time savings and midday demand on operational facilities confirms this pattern. A facility charging fifteen cents and one charging a dollar can both attract strong demand when customers trust they will get an uncongested trip. Thoughtful owners avoid policies that force minimum tolls so low that they suppress this value. Figure 1 illustrates how pricing functions under a soft cap regime of this type.

Commercial Consideration #2: Exempt Vehicles, Discounts, and HOV Policies

Many express lanes inherit High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) policies from the HOV lanes they replaced. Others establish their own discounts for HOVs, local users, electric vehicles, or specific groups such as veterans and low-income households. However, they arise, discount policies can significantly affect both operations and the revenue potential of a PML project.

Many PML P3s offer steep discounts or even free rides are offered to HOV2+ or HOV3+ vehicles. Drivers self-declare their HOV status before each trip, typically by switching a transponder or using a smartphone app. The system records this status at the tolling point, and the discount is often applied automatically.

Enforcement remains a challenge. No reliable technology exists to verify a vehicle’s HOV status, and local laws often restrict the actions operators can take against repeat violators. Manual enforcement by police officers stationed near toll gantries encourages compliance, but with violation rates reaching 30% on some express lanes, an officer can only catch a small fraction of offenders.

Emerging technologies promise more comprehensive enforcement. Camera and infrared systems can count vehicle occupants, yet no operator currently allows these systems to automatically process violations. Instead, the data is more often used to identify and pursue the most frequent offenders.

Beyond HOV discounts, owners may offer incentives to encourage certain behaviors or advance equity goals. As with HOV discounts, the enforcement, revenue impact, and effectiveness of these policies are often uncertain. Thoughtful owners aim to minimize the number of discounts and free rides, both to preserve operational integrity and to support the feasibility of the project.

A particular challenge arises when discount policies differ among facilities within the same region, potentially causing confusion for motorists, as seen in Northern Virginia. Coordinated policies, such as those developed by the North Central Texas Council of Governments, offer a model for consistency and clarity.

Commercial Consideration #3: Tolling Services and Violations Processing Agreements

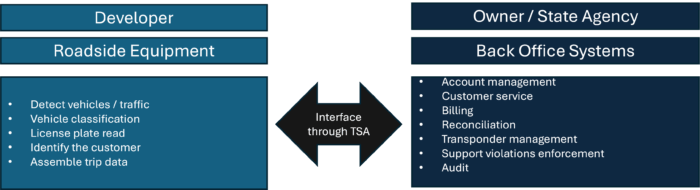

Most PML P3s adopt a Tolling Services Agreement (TSA), identifying the tolling responsibilities of the owner or the applicable publicly operated toll agency within the state. Key responsibilities of the developer and the state agency under a typical TSA are shown in Figure 2.

A TSA is intended to first ensure uniformity of approach to back office and business rules for customers and second to provide an efficient (and ideally consistent) service to bill customers and remit funds reliably based upon transactions that the developer transmits. While some developers can conduct these services in-house, a TSA is often mandatory, at least for an initial term.

Where there is an established history of toll usage in a jurisdiction, it is reasonable for the developer to estimate leakage and assume toll violations and/or collection risk. However, owners may still include within an PML P3 an optional form of violations processing agreement, the purpose of which is to offer the developer a state-provided violations service.

While there are several examples of executed TSAs that owners can use as a starting point, each TSA is unique to the policies, laws and practices of an individual state and it is never too early to develop a framework.

Two key early decisions deserve extended consideration. First, the transaction fee structure needs to be established, including how such fees will be adjusted year by year and as new technologies are adopted. This may include both fixed and variable fees on transactions.

Second, permitted tolling methods need to be determined. While administratively simple to require the adoption of an in-vehicle electronic tag, post-paid video tolling (known as pay-by-mail in Texas, for example) can encourage wider use of the system. Low frequency users without transponders can feel free to use the PML and are not immediately classified as “toll violators” or assessed large fines. On the other hand, collecting revenue from post-paid drivers can prove both expensive and difficult. We note that both the NTTA in Dallas-Ft Worth and NCTA in North Carolina have raised the multiplier on tolls that are assessed to non-tag transactions in recent years from 50% to 100%.

Conclusions

We have identified three key commercial considerations that owners should tackle early on when considering establishing or expanding a PML network. While these are fundamental to the outcome of a PML P3 project, owners face many other interconnected considerations. The next paper in this series addresses many of these planning factors. We encourage owners and the private sector to engage with each other and to share lessons learned with the broader developer, operator, and contractor market, and to develop robust teams of internal talent and experienced advisors to shape project and program policy.

John Brady, Jonathan Startin, and Noah Jolley are part of HNTB’s Advisory practice, focused on providing strategic and commercial advice for large transportation initiatives in the United States.