The United Kingdom’s privatized water industry is in a shambles. On the bright side, its government created a commission to sort out why. That Independent Water Commission led by Sir Jon Cunliffe completed its inquiry this summer, and this is the third of a series of articles diving into its 464-page report and dozens of recommendations. Our first article examined the commission’s bombshell recommendation to shutter and replace the water industry’s economic regulator, Ofwat. Our second article looked at what the commission had to say about water company dividends and executive bonuses.

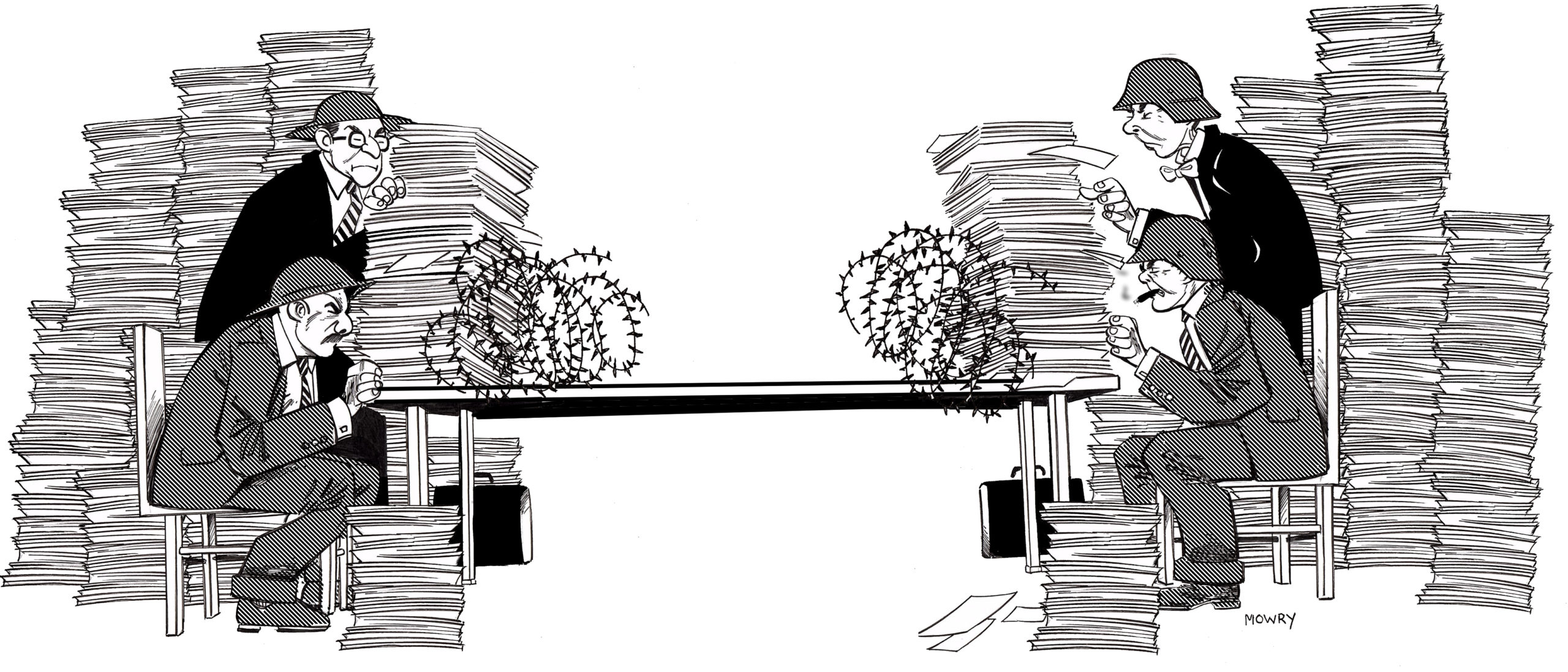

This third and final article examines the commission’s discussion of Ofwat’s regulatory practices, and specifically those that changed or were introduced over the last decade or so. This was a period in which Ofwat’s regulatory scheme over the water companies grew extraordinarily complex – even compared to other energy, water or wastewater regulated utility systems. Ofwat changed how it modeled company maintenance requirements and created new performance metrics and incentive programs for the industry. The Cunliffe commission went into detail examining every one. It is a nuanced, complex, and very boring read.

But the topic is important, and well beyond the survival of the UK’s privatized water industry. Everyone agrees that UK water industry has an underinvestment problem. Stormwater overflows are polluting the rivers and angering the British public. In addition, water bills are set to increase significantly over the next pricing period, as the water companies aim to catch up.

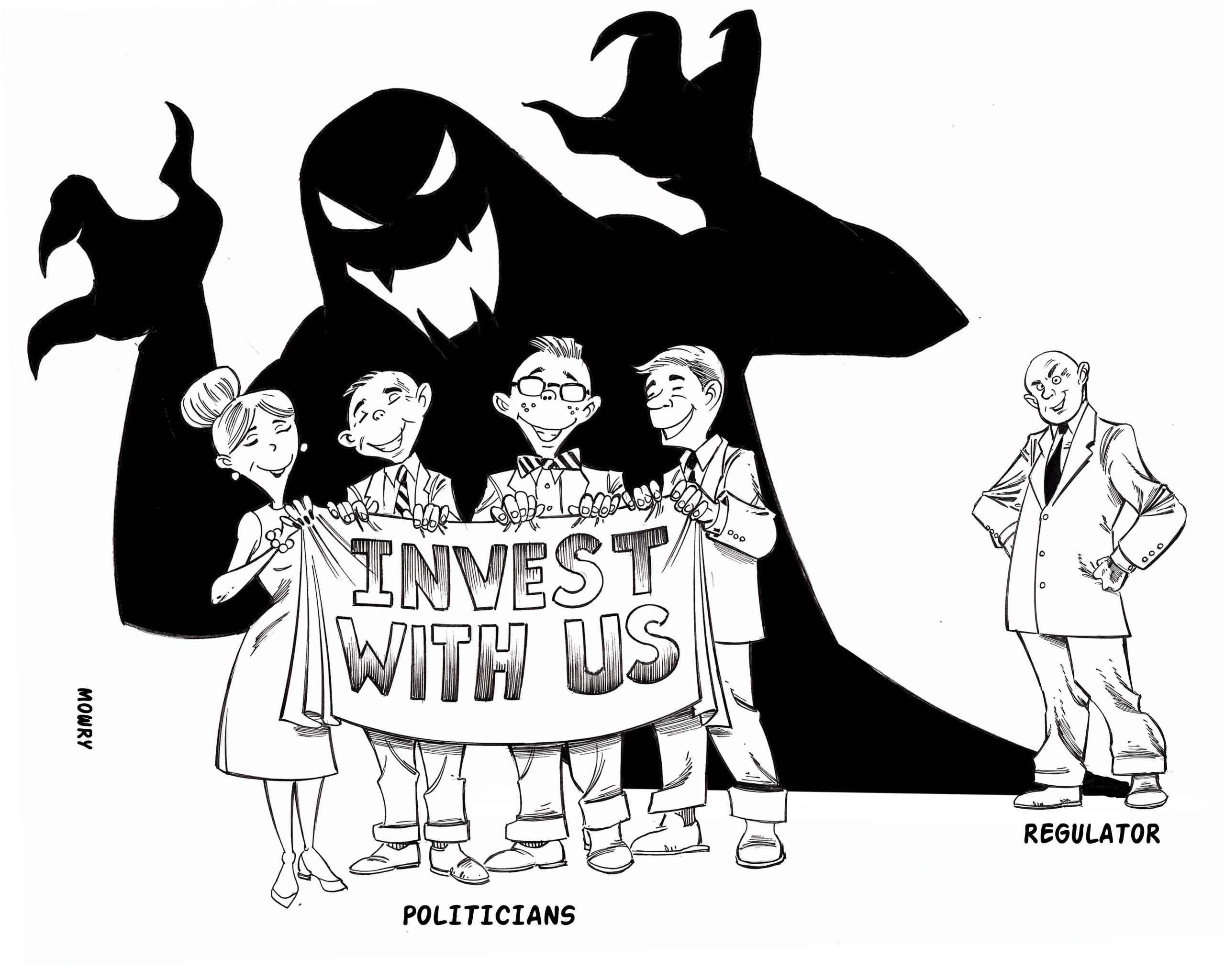

The important question is what went wrong. There are two broad explanations. The first is fairly simple and has clearly held sway among the British press and public. It is that investors in the water companies paid dividends and extracted profits instead of investing in infrastructure. Read this synopsis from the BBC, published just this month, for such an account. The Cunliffe commission certainly doesn’t dismiss this history outright.

This article explores a second, more complex explanation, which is that political pressure on Ofwat starting roughly 13 years ago pushed the regulator to focus on keeping water bills low, and which greatly expanded its regulatory powers. This had the effect of significantly increasing the complexity of Ofwat’s regulatory program while starving the industry of investment.