The British people have a right to be angry at the state of their water industry. And they certainly are. The industry featured heavily among voters in the UK’s recent election campaign, which resulted in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party.

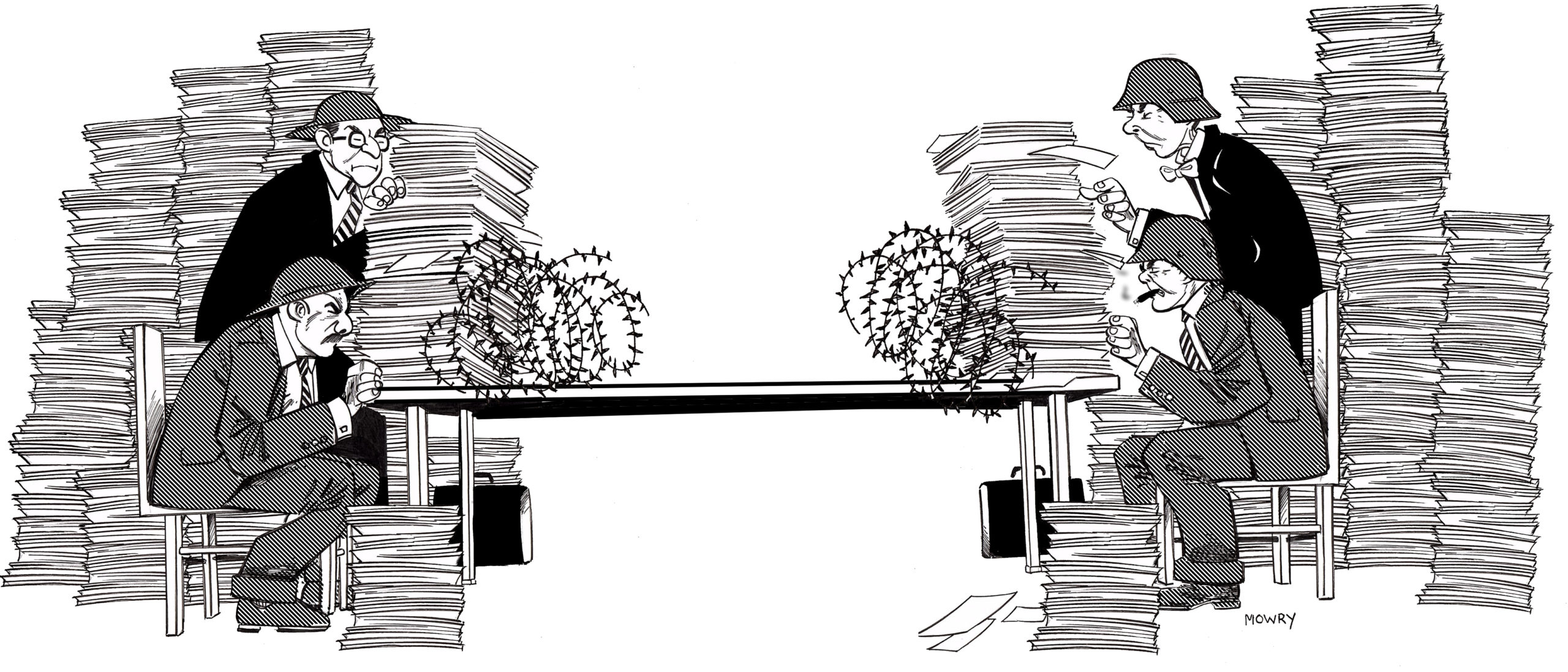

Things have only gotten worse for the industry, and Thames Water in particular, since then. After the election, Ofwat, the industry’s regulator, published its draft price reviews for the next five years of operations. The review placed Thames Water into a special turnaround oversight scheme, and criticized the firm’s business plan as “lacking ambition.” Across the sector, the draft decision would allow water bills to increase by approximately 21% on average, compared to the 33% requested in the industry’s investment plans.

By the end of the month, at least two more Thames Water investors (the UK’s own Universities Superannuation Scheme and the Queensland Investment Corporation) had announced that they were writing off their investments in the firm, and its senior most credit was downgraded to junk, placing Thames Water in breach of one of its license requirements.

The Thames Water saga is likely to continue for some time, and will not likely have a happy ending. Yet the story told to date: the story of why the UK water industry is failing, is arguably more important. It is a story that we’re likely going to hear again and again for a long time to come.

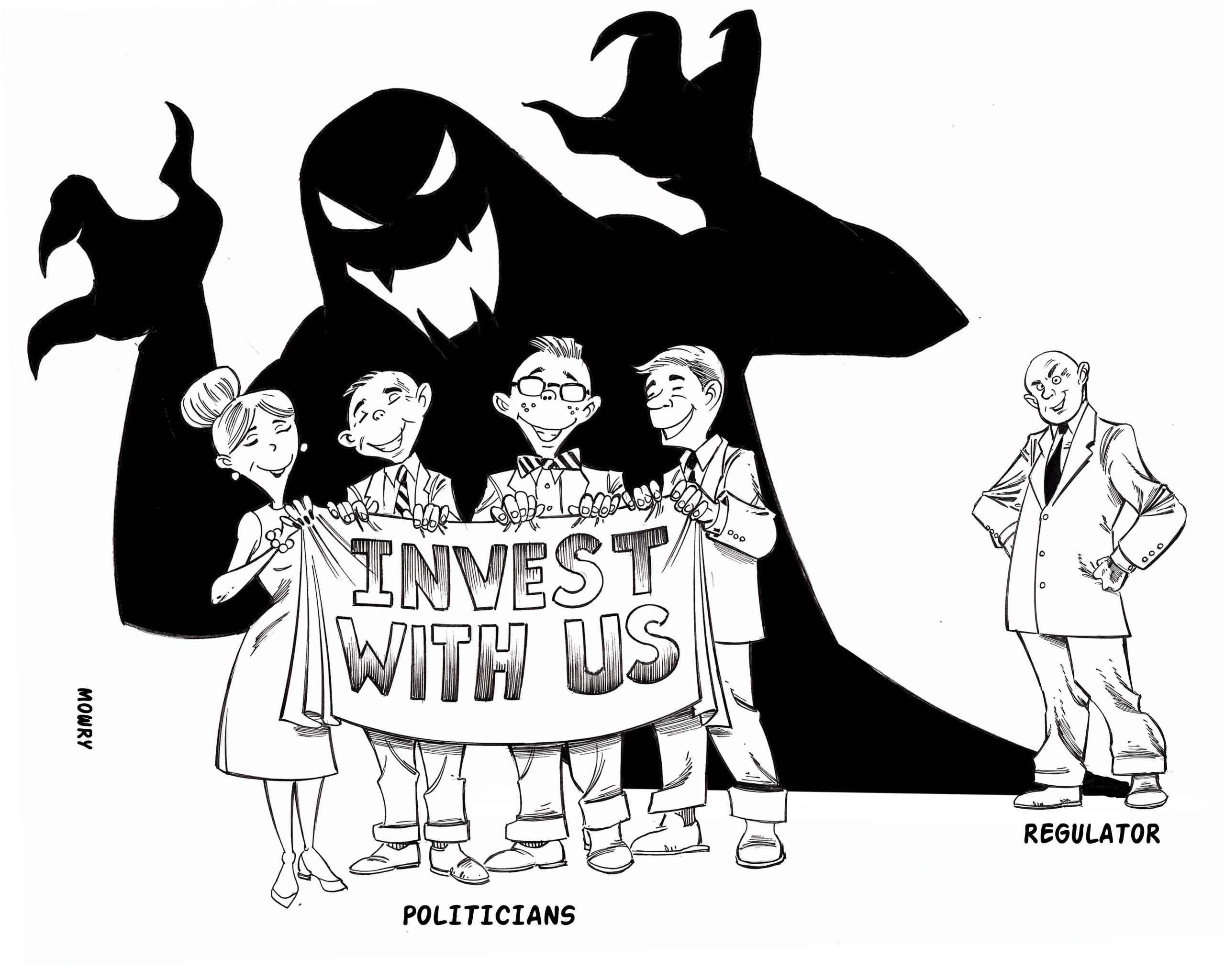

This article is about that story, or what one could call the “narrative” explaining the UK water industry’s plight, and why one explanation has become the consensus view. That narrative is essentially one about greedy investors, who loaded up water companies with unsustainable levels of debt in order to juice dividends while interest rates were low. And now that the industry is struggling, it is trying to stick customers with rate hikes and failing to prevent raw sewage from sullying the nation’s rivers.